In just under a week, full contact sport returns! Excited…..or scared…..or both? Maybe you’re itching at the chance of going toe to toe again and dominating the young under 20 future star and teaching him a thing or two about “your experience”. Or maybe you are that future star, and the urge to train as hard as ever and prove to the experienced/shoving on lads that experience will never match pace, speed and skill has you chomping at the bit.

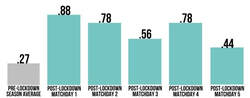

However, science tells us not to rush. Science tells us that training in a structured way may actually prevent against injury but excessive and rapid increases in training loads are likely responsible for a large proportion of non-contact, soft-tissue injuries (Gabbett, 2016). It’s the latter part of that statement that worries me, particularly in the return to sport environment we all now find ourselves in. While trawling through Twitter recently I came across the trackademic blog that referenced the below graphic. I did lose sleep over it. It’s from a study of the return of the Bundesliga and the injury rates in matches since that return. These guys are professional athletes with every resource under the sun available to them. I’m presuming they had decent levels of fitness pre-covid and resources to at least maintain during the enforced off season. It’s definitely a statistic to chew on/cry over and plan for in your upcoming re championship training.

However, science tells us not to rush. Science tells us that training in a structured way may actually prevent against injury but excessive and rapid increases in training loads are likely responsible for a large proportion of non-contact, soft-tissue injuries (Gabbett, 2016). It’s the latter part of that statement that worries me, particularly in the return to sport environment we all now find ourselves in. While trawling through Twitter recently I came across the trackademic blog that referenced the below graphic. I did lose sleep over it. It’s from a study of the return of the Bundesliga and the injury rates in matches since that return. These guys are professional athletes with every resource under the sun available to them. I’m presuming they had decent levels of fitness pre-covid and resources to at least maintain during the enforced off season. It’s definitely a statistic to chew on/cry over and plan for in your upcoming re championship training.

(Mason J, trackademicblog.com, 2020)

Whichever category you fall into, the young gun or the seasoned player, it’s important you know that it won’t be a matter of just dusting off the boots and returning to the same intensity that we finished at on March 12th. It’s also important that you know that the 2 x 5k runs weekly and the online core class isn’t going to sustain you unscathed through a 60 minute in house match on June 30th. The build up to return to championship is such a short window. I realise coaches and players need and want to maximise this time, but that may come at a cost. That cost being injury, poor training intensity, and ultimately, poor performance. Now, possibly more than ever, listening to your body (and your physio/AT!) is so important.

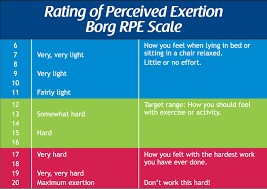

In order to help you understand what your body is saying to you, there are a number of tools we can use to monitor training load and ensure we’re getting the best out of a session without putting ourselves at risk. While not every club has access to GPS units, performance analysis, pre championship screening (I got laughed at when I suggested this one!), the simple to use RPE may just be what we need to get us to county final day relatively unharmed!

RPE or Rate of perceived exertion has been around for years and has stood the test of time. It was developed by Borg in 1977 and is an acceptable measure of exercise intensity today. It is a measure of your perceived exercise on a scale of 6-20.

In order to help you understand what your body is saying to you, there are a number of tools we can use to monitor training load and ensure we’re getting the best out of a session without putting ourselves at risk. While not every club has access to GPS units, performance analysis, pre championship screening (I got laughed at when I suggested this one!), the simple to use RPE may just be what we need to get us to county final day relatively unharmed!

RPE or Rate of perceived exertion has been around for years and has stood the test of time. It was developed by Borg in 1977 and is an acceptable measure of exercise intensity today. It is a measure of your perceived exercise on a scale of 6-20.

(American College of Sports Medicine, 2010)

There have been a number of variations on the Borg scale since and a revised scale of 0-10 is now also used.

(American College of Sports Medicine, 2010)

(American College of Sports Medicine, 2010)

For the purpose of this blog, I’m going to focus on and explain the session rating of perceived exertion. This allows a player to rate the intensity of their exercise session but also takes into account the number of minutes within that particular session. At the end of a training session, athletes give a 1-10 rating on the “intensity” of the session. This rating is then multiplied by the duration of the session to give a figure for internal training load. The unit of measurement is “RPE load x minutes” and the range given for field sport athletes (soccer players) is a range between 300-500 for low intensity sessions and 700-1000 for higher intensity sessions (Gabbett, 2016). It’s worth noting that RPE is the athlete’s perception of effort, and perception can be affected by many factors (genetics, needs, peers, mood, expectations…… the list goes on!)

Many studies have revealed that higher training loads were associated with greater injury rates (Anderson et all, 2003; Killen et al, 2012). 40% of injuries were associated with a rapid increase in training load in a period of 1 week (>10%) (Piggot et al, 2009). Large changes in training loads within one week (1069 RPE Load x minutes) also led to an increased risk of injury in the professional rugby player (Cross et al, 2015).

Whilst the majority of this data was collected amongst elite athletes, I feel an awareness of the patterns observed is imperative for the amateur athlete and their coaches, particularly with the current climate of a long lay off and a shortened run up to championship matches. Implementing a load monitoring system may be one of the factors that could decrease injury risk in our athletes. But it is important to remember that it is only one tool in an array of methods that can aid training, recovery and internal and external loading of players. As with all aspects of sport, training, recovery, rehabilitation and performance are all multifactorial. However, it’s definitely not one to ignore though for the 2020 pre-season part 2!

So what’s the take home? I’m not saying that we keep all our internal training load measurements at the lower end of the scale. We know that training at high intensity, with strength and power, can protect against injury – but it’s the rapid increase in training loads is the worry, or in plain English – too much too soon! Sessions with an RPE x minutes reading in the 1000’s should be interspersed with lower intensity sessions – so we’re still training hard – just on Tuesday night though and not again on Thursday and Sunday. I hope this resonates with both players and coaches alike. We know intentions are good and the will to work hard is there for most but the all out approach may come back to bite you in the behind come championship time when the team physio keeps adding names to that injury list. So think about it, implement it, seek advice with it and maybe there’ll be a full panel available for selection to give you another headache come championship game round 1!

References

American College of Sports Medicine (2010). Heart online scale. https://www.heartonline.org.au/ [accessed 20/06/2020]

Anderson L, Triplett-McBride T, Foster C. Impact of training patterns on incidence of illness and injury during a women's collegiate basketball season. J Strength Cond Res 2003;17:734–8

Cross MJ, Williams S, Trewartha G. The influence of in-season training loads on injury risk in professional rugby union. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2015 (in press)

Gabbett TJ. The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;50:273-280.

Killen NM, Gabbett TJ, Jenkins DG. Training loads and incidence of injury during the preseason in professional rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:2079–84.

Mason J, The Bundesliga Blueprint: the snapshot becomes a story, 2020. Trackademicblog.com [accessed May 20th 2020].

Piggott B, Newton MJ, McGuigan MR. The relationship between training load and incidence of injury and illness over a pre-season at an Australian Football League club. J Aust Strength Cond 2009;17:4–17

Many studies have revealed that higher training loads were associated with greater injury rates (Anderson et all, 2003; Killen et al, 2012). 40% of injuries were associated with a rapid increase in training load in a period of 1 week (>10%) (Piggot et al, 2009). Large changes in training loads within one week (1069 RPE Load x minutes) also led to an increased risk of injury in the professional rugby player (Cross et al, 2015).

Whilst the majority of this data was collected amongst elite athletes, I feel an awareness of the patterns observed is imperative for the amateur athlete and their coaches, particularly with the current climate of a long lay off and a shortened run up to championship matches. Implementing a load monitoring system may be one of the factors that could decrease injury risk in our athletes. But it is important to remember that it is only one tool in an array of methods that can aid training, recovery and internal and external loading of players. As with all aspects of sport, training, recovery, rehabilitation and performance are all multifactorial. However, it’s definitely not one to ignore though for the 2020 pre-season part 2!

So what’s the take home? I’m not saying that we keep all our internal training load measurements at the lower end of the scale. We know that training at high intensity, with strength and power, can protect against injury – but it’s the rapid increase in training loads is the worry, or in plain English – too much too soon! Sessions with an RPE x minutes reading in the 1000’s should be interspersed with lower intensity sessions – so we’re still training hard – just on Tuesday night though and not again on Thursday and Sunday. I hope this resonates with both players and coaches alike. We know intentions are good and the will to work hard is there for most but the all out approach may come back to bite you in the behind come championship time when the team physio keeps adding names to that injury list. So think about it, implement it, seek advice with it and maybe there’ll be a full panel available for selection to give you another headache come championship game round 1!

References

American College of Sports Medicine (2010). Heart online scale. https://www.heartonline.org.au/ [accessed 20/06/2020]

Anderson L, Triplett-McBride T, Foster C. Impact of training patterns on incidence of illness and injury during a women's collegiate basketball season. J Strength Cond Res 2003;17:734–8

Cross MJ, Williams S, Trewartha G. The influence of in-season training loads on injury risk in professional rugby union. Int J Sports Physiol Perform 2015 (in press)

Gabbett TJ. The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;50:273-280.

Killen NM, Gabbett TJ, Jenkins DG. Training loads and incidence of injury during the preseason in professional rugby league players. J Strength Cond Res 2010;24:2079–84.

Mason J, The Bundesliga Blueprint: the snapshot becomes a story, 2020. Trackademicblog.com [accessed May 20th 2020].

Piggott B, Newton MJ, McGuigan MR. The relationship between training load and incidence of injury and illness over a pre-season at an Australian Football League club. J Aust Strength Cond 2009;17:4–17

RSS Feed

RSS Feed